Misfolding of the brain is linked with many neurological conditions including autism, anorexia, epilepsy and schizophrenia.

Premature birth and foetal growth restriction, major risk factors for cerebral palsy, can also affect brain folding and lead to cognitive deficits.

While we know folds are essential to how a healthy human brain works, scientists are only beginning to understand what drives the folding process and why it goes wrong.

A new pre-clinical study by Australian and Swiss researchers has for the first time identified the genes linked with the development of the two types of brain folds – inward and outward – in the grey matter of the brain.

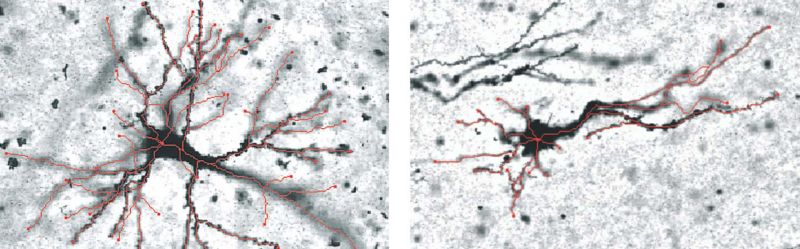

Using animal models that closely resemble human brain development, the study found differences in both genetic expression and neuron shape during the folding process.

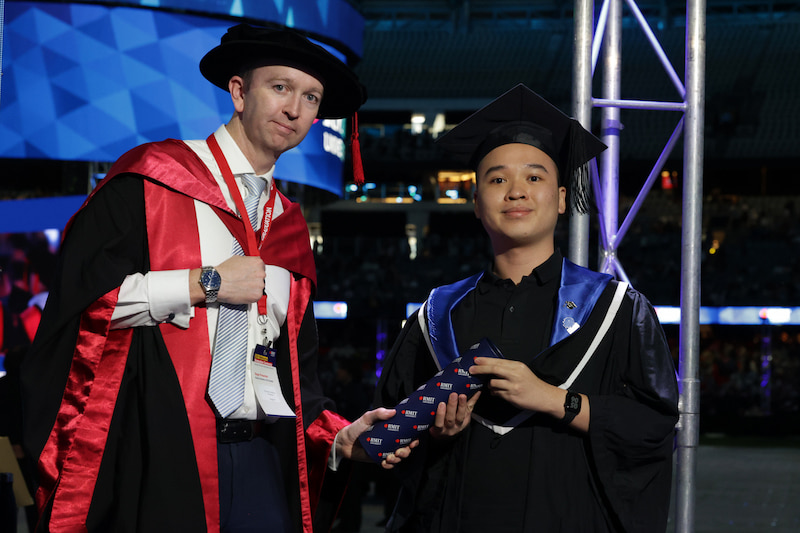

Co-chief investigator Associate Professor Mary Tolcos, RMIT University said there were currently no therapies for the prevention or treatment of brain misfolding and no early test to detect problems before folding begins.

“We know folding happens in the second and third trimester of pregnancy and that all human brains fold along largely the same patterns,” said Associate Professor Tolcos, an Australian Research Council Future Fellow at RMIT.

“This suggests the process is heavily controlled by our genes but we’re only starting to understand how – it’s like having an intricately folded piece of origami that’s missing the instructions.

“Our study is a critical step towards fully understanding those genetic instructions, by pinpointing which genes are linked with fold development.

“The next step is to determine the precise role these genes play in the process, so we can work towards identifying potential therapeutic targets and develop interventions to prevent and fix misfolding in the brain.”

Folding fundamentals

Previous brain folding studies have focused on white matter or looked at animals with smooth brains rather than folded ones, but have largely overlooked grey matter.

Grey matter is made up of neuron bodies and their connecting arms, while white matter is composed of the neurons’ long nerve fibres and their protective layer of fat.

While the science of folding is still unclear, the latest evidence suggests grey matter in the developing brain expands faster than white matter, creating mechanical instability that leads to brain folding.

But the resulting ‘hill’ and ‘valley’ folds are not random – they follow a similar pattern in all folded brains of the same species.